Editor of this issue: Violeta Kelertas

Copyright © 2007 LITUANUS Foundation, Inc.

|

LITUANUS

LITHUANIAN

QUARTERLY JOURNAL OF ARTS AND SCIENCES

Volume 53, No.2 - Summer 2007

Editor of this issue: Violeta Kelertas ISSN 0024-5089

Copyright © 2007 LITUANUS Foundation, Inc. |

|

Power Lines and Pipe Dreams: Energy and Politics in Lithuania

Vincentas Rolandas Giedraitis

Vincentas Rolandas Giedraitis is an assistant professor in the Department of Economic Theory at Vilnius University in Lithuania. He received his Ph.D. in 2006 from the University of California, Riverside and is the managing editor of the journal Ekonomika. His current research interests include geopolitical dependency relations in post-socialist countries and macroeconomic factors contributing to suicide in Lithuania. He is a former Fulbright scholar and his research appears in journals including Research in International Business and Finance, Sociological Focus, and Social Justice.

Who controls the energy sources controls

the fate of nations.

Henry Kissinger

“Energy politics” have been used by Russia not only in Lithuania, but as recently as January 2007 in Ukraine, Georgia, and Belarus as well. Russia claims that its motives are market driven, seeking to simply increase the price of oil to market values. An alternative explanation is that, Russia, eager to extend its sphere of influence over its “lost territories,” is using the so-called “energy weapon” (Smith 2005) – dependence on Russian oil – to foster a condition of economic imperialism over the region. Energy dependence is a new form of Russian imperialism, not only in the Baltic States, but in Western Europe as well. This essay on economic policy in Lithuania surveys the current condition of energy dependency, its relationship to politics in Lithuania, and possible solutions to the dependence problem. Dependency on a primary resource is dangerous due to the perils of the flow of oil being disrupted, as was the case during Lithuania’s early independence.

Introduction

Geopolitically, energy dependency is one of the most challenging issues facing Lithuania today, because the country is so reliant on oil from foreign sources. A steady supply of oil is essential to Lithuania’s economy, since the country’s primary exports are refined petroleum products. In fact, the issue of energy dependence for the entire European Union has been a serious problem since the global energy crisis of 1973-1974. Now, as a part of the European Union, Lithuania’s general energy concerns are more in line with the rest of Western Europe, although its specific situation, as this paper will indicate, is quite different.

Lithuania’s dependence on Russian energy is due to a lack of energy diversity. The changes in energy dependence Lithuania has displayed over the past fifteen years are the products of new resources and dependency relations following the breakup of the Soviet Union. For example, Lithuania was not able to freely trade with the West as a Soviet Socialist Republic. However, now, as a part of the European Union and NATO, Lithuania continues to import crude oil from Russia. Russia possesses vast stores of oil, and recent high global prices for oil have contributed to some extent to its growing economy. However, Western Europe and former socialist-satellite republics, such as Lithuania, are as dependent as ever on a plentiful and reliable Russian oil supply. Although Norway possesses half the oil reserves in Europe, its oil prices are nonetheless higher than Russia’s. This is because it lacks the infrastructure to transfer Russian oil to the former Soviet satellites (Hagland 2000). Because the European Union is pressing Lithuania to shut down both of its Chernobyl-style nuclear reactors by 2009, its unique status as a net electricity exporter will be replaced with the unenviable position of even greater reliance on Russian oil.

The country is a member of NATO, the most powerful military bloc on earth, and its membership in the EU has brought economic prosperity and an influx of foreign investment, factors leading it on a trajectory to the relatively high standards of living that the country enjoyed during its inde58 pendence between the world wars. Additionally, the peaceful and democratic impeachment of former President Paksas in 2003 – the first president to be impeached in European history – gained worldwide attention and showed that the country could endure one of the most challenging of constitutional crises without bloodshed or even minor socioeconomic disruptions. This economic stability and growth in Lithuania, as in other countries, are solidly grounded in a steady supply of energy. Russia, however, is engaging in a new form of neocolonialism using energy rather than the military as a weapon (Smith 2005).

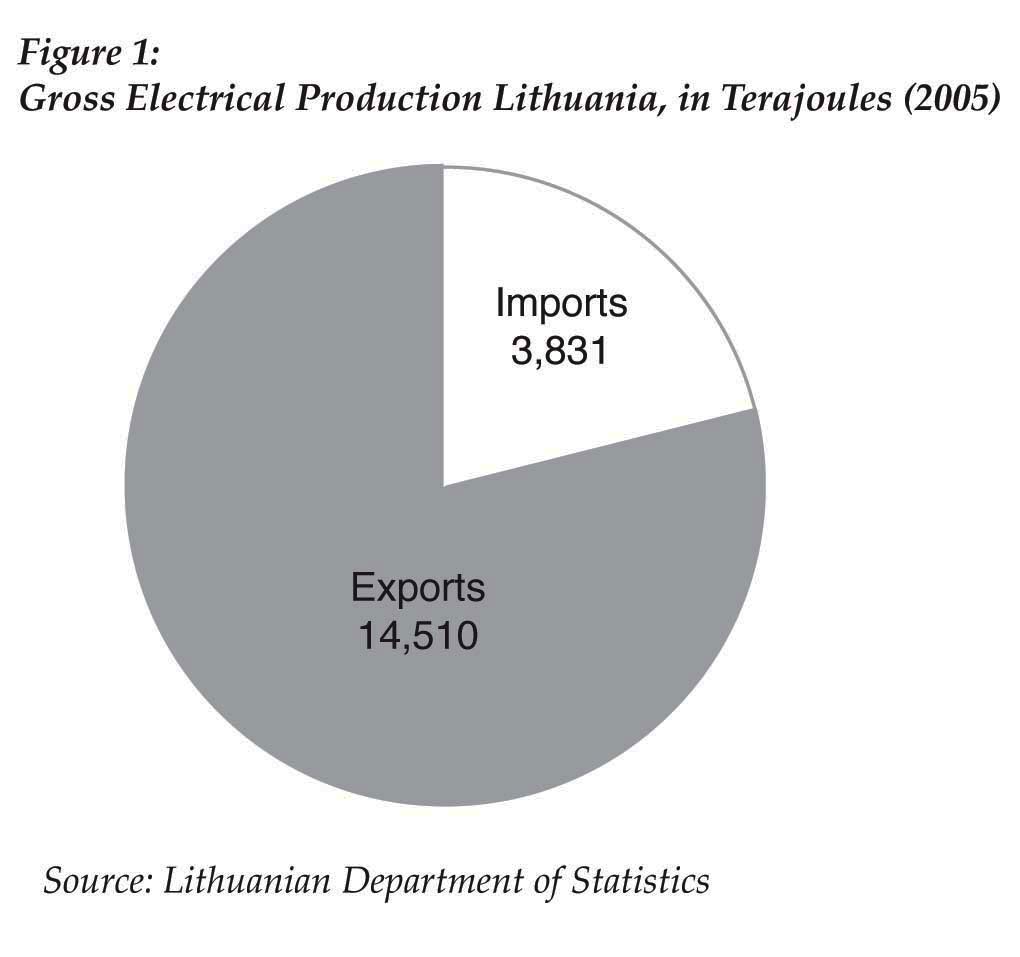

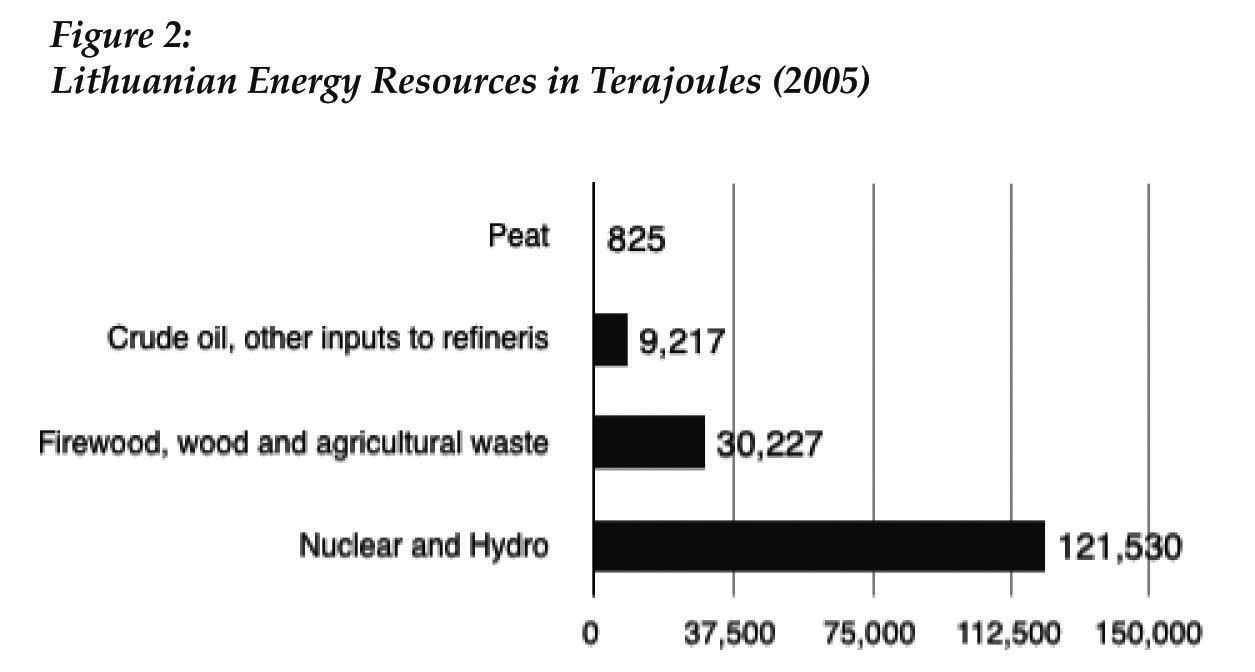

Due to its Ignalina nuclear power plant, Lithuania is unique in being a net exporter of electrical power (see Figure 1), and its natural reserves of crude oil are very small (see Figure 2). Thus far, the issue of electrical power is not as serious as that of crude oil, although Ignalina is to be shut down by 2009. Lithuania has expressed interest in the construction of a new nuclear facility, with EU assistance, to be built by a French firm.

|

|

Latvia imports the most electrical power of all the Baltic countries, but is working with Estonia and Finland to develop the “Estlink” project, a 315-megawatt underwater cable linking the Baltic States to the Scandinavian and Nordic electrical power grids, to reduce reliance on Russia for energy. In addition to Estlink, various other proposals to create regional links among the Baltic countries have been presented by Scandinavian firms. For example, the Powerbridge Project between Lithuania and Poland would allow the export of Ignalina’s electricity surplus to Germany and the rest of Western Europe. External issues have plagued the Lithuania-Poland connection: Russia has suggested that it may undercut the Lithuanian price of power to Western Europe if it moves ahead with building the necessary infrastructure (Huang 2002; Smith 2005).

Latvia’s electrical power is primarily generated by a number of hydroelectric dams generating roughly 1515 MW, though the country is entirely dependent upon favorable weather in its generation of electrical power. For example, in 1999, a drought year, Latvia was forced to import 1 TWh of electricity, or about 23 percent of its total demand. To exacerbate the situation, LatFigure 2: Lithuanian Energy Resources in Terajoules (2005) Source: Lithuanian Department of Statistics via had little ability to connect directly to the rest of Europe’s power grid. Due to its relatively unstable position among the Baltic States in the energy sector, Latvia has placed a very high priority on its energy generation capabilities (Huang 2002).

Lithuania depends on Russia for its supply of natural gas as much as crude oil. Energy dependency on Russia varies among the Baltic countries, however, because each has different forms of natural resources and infrastructure. For example, Estonia is blessed with a plentiful supply of oil shale. In 2002, Lithuania and Estonia produced roughly 5,000 barrels of crude per day. Ironically, it was the Soviets who made Estonia self-sufficient in electricity (Huang 2002). The 1390 MW Baltic power plant built in 1959 and the 1610 MW Eesti power plant built a decade later provided Estonia with nonnuclear electrical self-sufficiency after Soviet rule. Latvia does not have any oil resources and is entirely dependent on imports (Huang 1999b).

Due to each Baltic country’s particular strengths and weaknesses in the energy sector, and facing a common potential threat from the East, the Baltic States have been working closely together to assist each other in improving their inherited energy infrastructures. Following the collapse of the Soviet Union, outdated Soviet transmission lines were replaced with more reliable ones that wasted much less power. Two 330kV lines now connect Latvia with Estonia, and four 330kV lines connect Latvia and Lithuania (Huang 2002).

Lithuania had to make difficult energy decisions on its road towards European Union membership. As a tradeoff for faster entry to the EU, Lithuania agreed to eventually close Ignalina, thereby giving up its primary power source. Alternatively, Lithuania could have remained the net electrical exporter in the region, but jeopardized its chances of swift EU entry, and certainly incurred further anger from the Western European community for continuing to operate the Chernobyl-style RBMK-2 reactors.

Construction of a third reactor was begun by the Soviets in 1983, but abandoned in 1989 (Misiūnas and Taagepera 1993). Ignalina initially generated 3000 MW of power. Under the com61 mand economy of the Soviet Union, it was designed to provide enough electricity to be a regional power source for that corner of the USSR. Besides Ignalina, Lithuania also operates the nonnuclear Soviet-era 1800 MW Elektrėnai power plant, which serves as a back-up to Ignalina whenever it goes off line for maintenance (Smith 2005).

Ironically, the planned Soviet expansion of Ignalina was a galvanizing force in the Lithuanian drive towards political independence (Misiūnas and Taagepera 1993). The very decision to build Ignalina was made at a high level in Moscow, without any input from the Lithuanian SSR. Ignalina was to have a total of four reactors – envisioned to be the largest nuclear reactor system in the Soviet Union. Although the USSR was clearly not oil-poor, more electrical resources would translate to a higher percentage of oil available for its military-industrial complex. The Chernobyl nuclear accident in the Ukraine in 1986 caused widespread fear of nuclear power and anger from Lithuanians, who became increasingly aware of Moscow’s master plans through Gorbachev’s concurrent policies of glasnost and perestroika. Ignalina is 600 kilometers southeast of Stockholm; 575 kilometers east of Copenhagen; 1750 kilometers east of Hamburg; 485 kilometers northeast of Warsaw, and only 180 kilometers north of Vilnius. Thus, a nuclear disaster there would have far-reaching consequences for all of Europe but could be catastrophic for Lithuania. The construction of the third reactor was successfully stopped due to mass demonstrations organized by Sąjūdis and the Greens. In one such demonstration in September 1988, 20,000 Lithuanians encircled the plant, making a human barrier and hindering construction operations (Kirby 1995).

The Politics of Ignalina

The fast or slow track to the European Union, dependent on Ignalina, was clearly a difficult decision for the world’s most nuclear-dependent nation. Then Economic Minister Vincas Babilius proposed two plans: one, with early shutdown in 2005; the other, with no early shutdown. Lithuania successfully lobbied for extensive EU financial support for early shutdown (Huang 1999a). A 1999 poll indicated that 80 percent of Lithuanians did not want Ignalina shut down. A poll taken the same year asked Lithuanians for their views towards EU entry, just after the European Commission completed its intensive campaign to persuade the Lithuanian public to agree to a shutdown of Ignalina: only 27 percent voted in favor of EU entry if it was contingent on shutting down Ignalina.

| Figure 3: Ignalina Nuclear Power Plant |

|

| Source: Author’s personal photograph (5/14/2004) |

The Lithuanian-American President, Valdas Adamkus, also took a firm position on the issue. He argued that building a new, safer, Western-style reactor to replace the Soviet reactors was the best choice for Lithuania and Europe. But closing the second reactor by 2009, said Adamkus, would be “signing and committing to the total bankruptcy of the country” (Frierson 2002). The EU, however, had had enough of demands from states that were not even a part of the European Union yet. Then Commissioner for Energy, Loyola de Palacio, remarked about Lithuania’s demands, “if this is the kind of thing they say before they are in the EU, what will they say after they are in?” (Bradley 2002). Simply closing Ignalina would be extremely expensive. It was estimated by the Lithuanian government that a complete shutdown would cost 2.4 billion euros. The fund that the government had been cobbling together had less than 2 percent of that amount, and it was clear that Lithuania would not be able to shut down Ignalina on its own (Bradley 2002). Despite the strong words of Lithuanian politicians, they were unable to gain concessions; and the stronger EU countries were forcing Lithuania into capitulation on the issue.

Ignalina generated not only power for the country, but revenue. While campaigning for EU entry, Lithuania had been exporting its electrical power to Belarus, which had an overall debt of 90 million USD to Lithuania for previously imported electricity (Huang 2002). As Lithuania moved politically Westward, it would have been able to export Ignalina’s power to more financially reliable Western European countries in a proposed Polish-Lithuanian power grid that could have generated 150 million USD per year for Lithuania.

Russia’s “Energy Weapon”

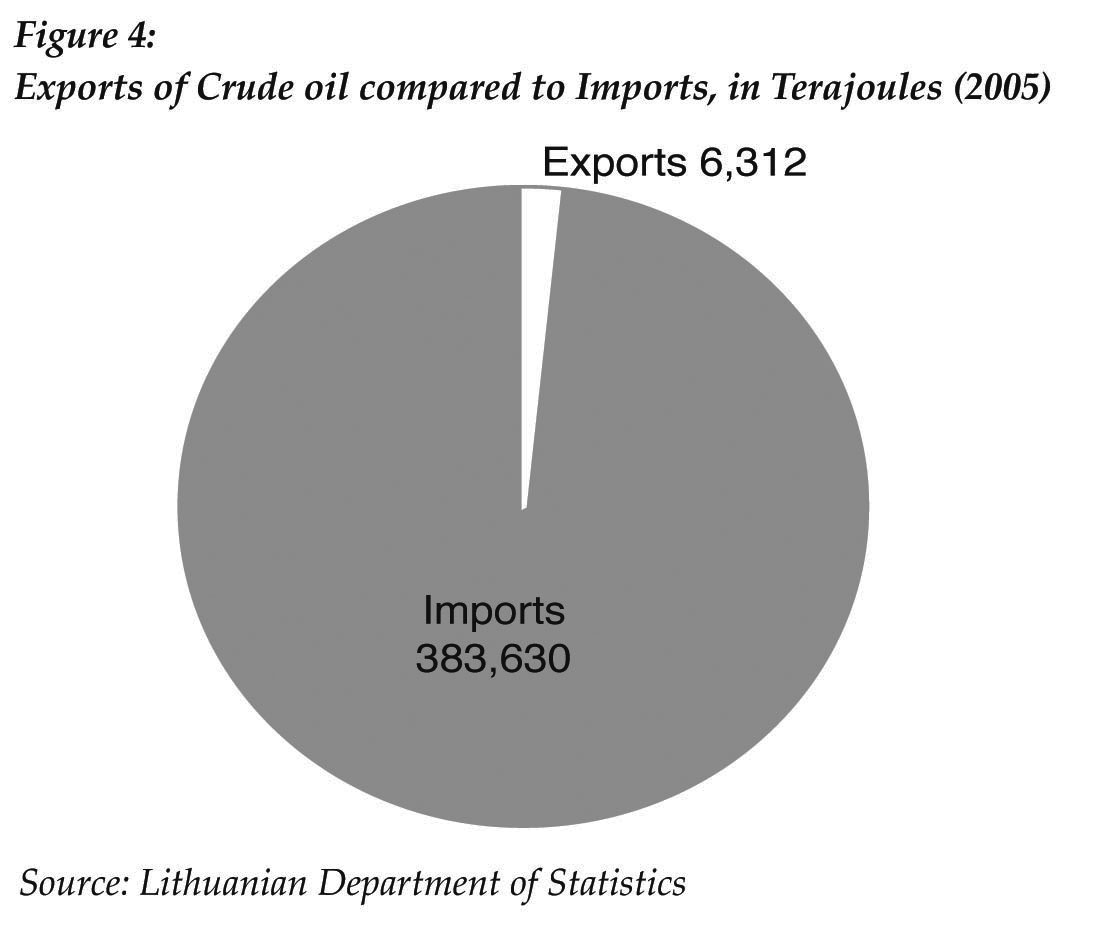

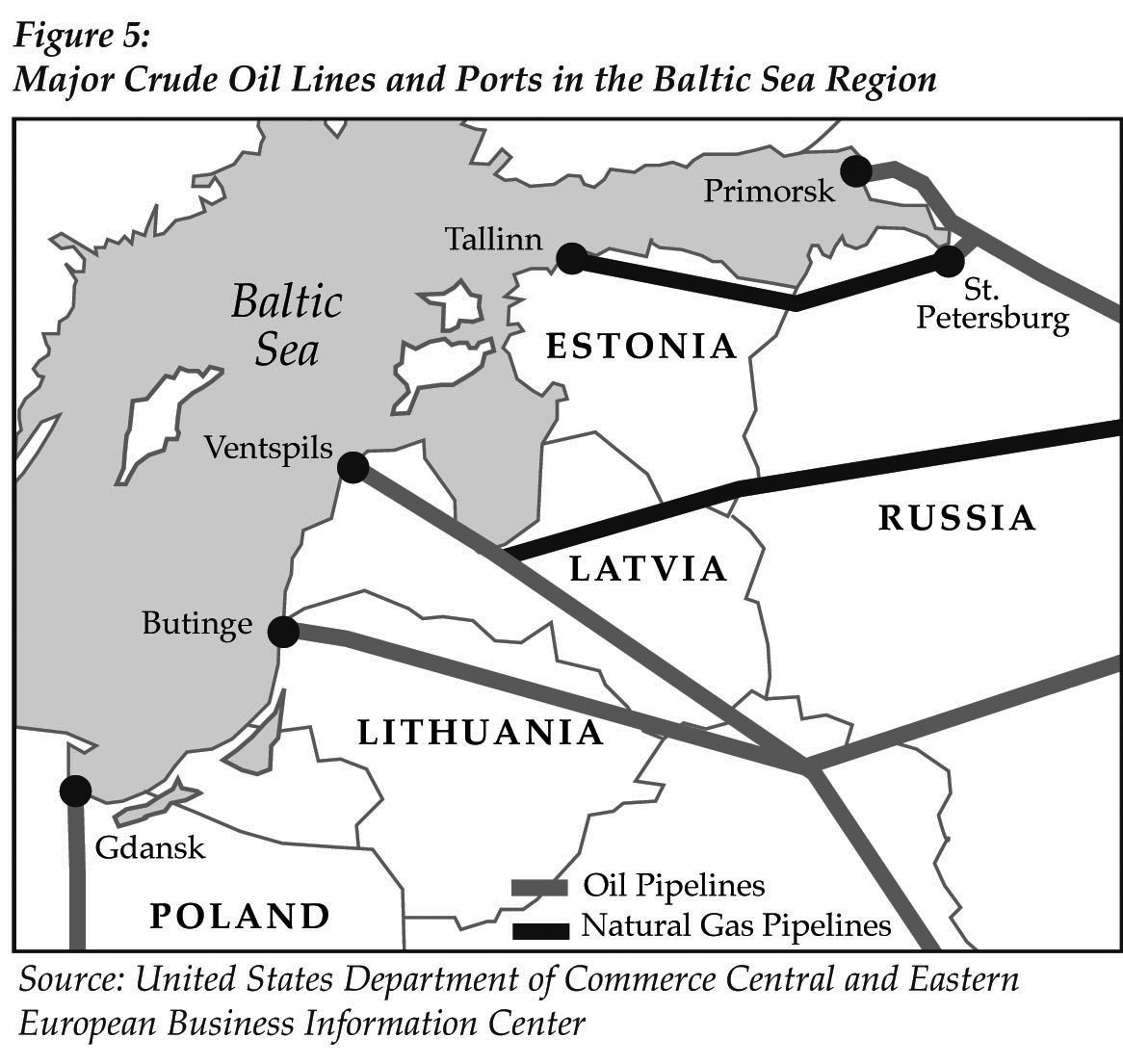

Natural resources have increasingly become a tool Russia is using for foreign policy goals (Niblett et. al. 2005; Smith 2005). It uses Lithuania’s oil dependency as a means to further its neocolonial foreign policy by keeping Lithuania under its sphere of influence. Indeed, although Russian politicians are calling on its government to diversify its economy, the major source of Russia’s economic growth is due to exports of oil and natural gas, especially during recent years of global energy insecurity. Figure 4 shows the relative exports and imports of crude oil from Lithuania, and Figure 5 shows the Russian pipeline system in the region. The three ports of Ventspils in Latvia, Būtingė in Lithuania, and Primorsk in Russia export about 10 percent of Russia’s total crude oil output (approximately 500,000 barrels per day in 2002).

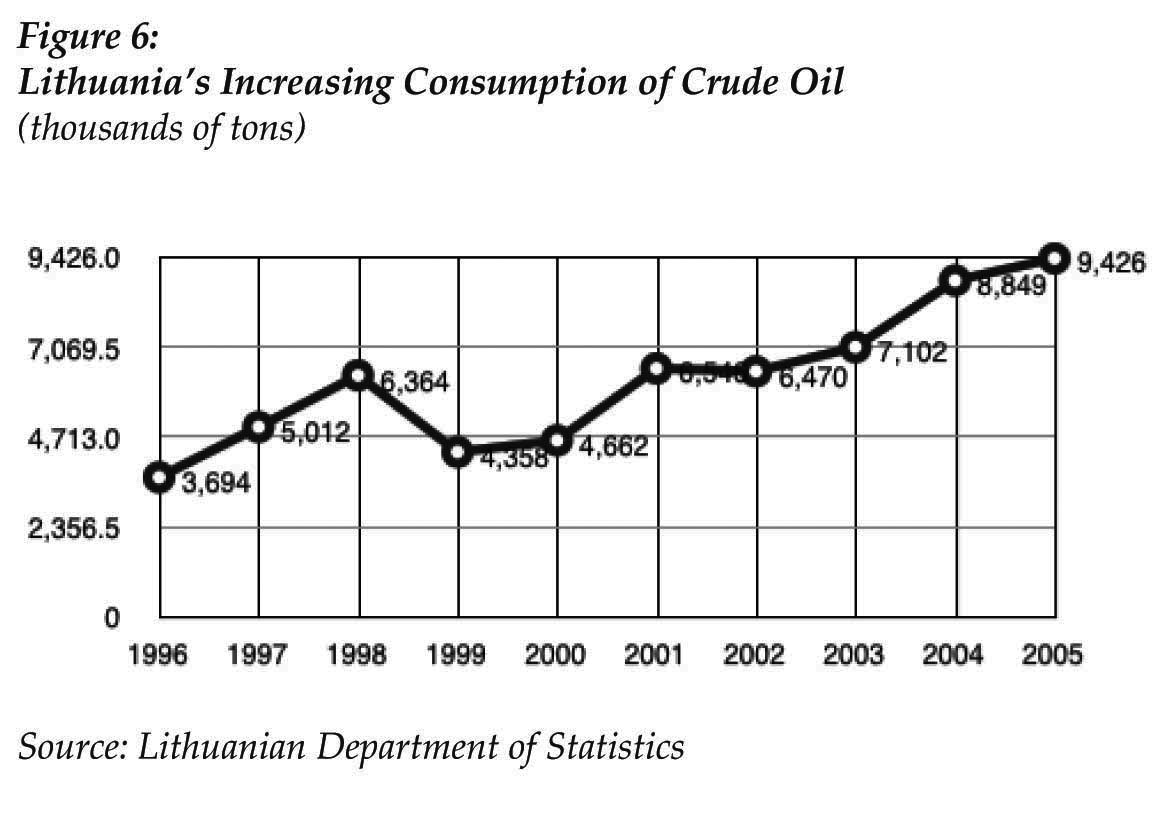

The Baltic countries depend on Russia for approximately 90 percent of their oil supply. Further, as Figure 6 indicates, demand is increasing as Lithuania becomes increasingly indus- trialized, further increasing demand. Lithuanian industry di- rectly relies on crude oil for producing such exports as plastics. Crude oil also provides the bulk of the vital central heating fuel during the cold winter months.

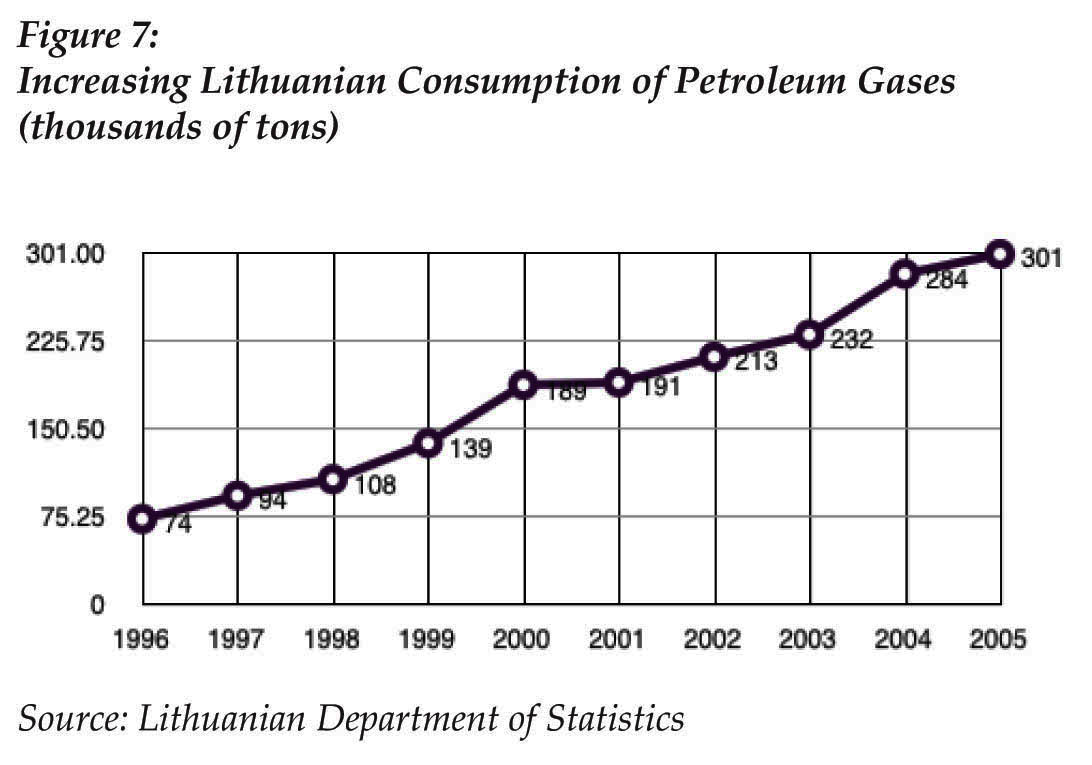

Figure 6 shows that since 1996, Lithuanian consumption of crude oil has almost tripled. The clear dip in 1999 is attribut- able to the Russian economic crisis of that year. The steadily increasing consumption after that, however, indicates the resil- ience of the Lithuanian economy as Western investment contin- ued to increase, driving oil consumption up again. The produc- tion of many Lithuanian exports similarly requires specialized forms of energy, namely liquefi ed petroleum gases, which are also imported from Russia. The increase in demand for liquefied petroleum gases is indicated in Figure 7.

Russia was quick to unleash its energy weapon during the turbulent year of 1990, when it shut off supplies to crush the independence movements of the Baltic Soviet Socialist Re- publics. During 1992 and 1993, Russia had again shut off oil exports to the Baltic States, allegedly due to a problem of over- pricing, yet the true reason was political (Smith 2005). In 1992, the threats to cut off the oil supply came directly from Russian companies that were reacting to the nonpayment of Baltic debt for fuel already consumed. The fi nancially poor postindepen- dence Baltic States were not able to pay Russia back immedi- ately for the oil they were using. As a warning sign to pay for oil already consumed, the oil supply at Lithuania’s Mažeikių Nafta was turned off for fi ve hours (Lithuanian Radio 1992a). Both Latvia and Lithuania were being pressured to pay for gas supplies over the summer, with a threat from the Russian fi rm Lentransgas that oil would be shut off during the critical heat- ing months of the winter. Russia was exploiting the small sup- ply of heating oil that it had traditionally provided to the Baltic region.

Russian Influence over the Lithuanian Energy Sector

The Russian government plays an active role in the coun- try’s strategic vision for energy, which is one of its greatest exports, as a geopolitical tool, and also has the goal of increasing exports of crude at market prices. Russian energy policy is a global enterprise. It is working on a network of oil pipelines to supply China, which, after the United States, is now the world’s second greatest importer of oil. India’s booming economy is also fueled increasingly by imported oil. Thus, to its benefit, Russia is surrounded by fuel-hungry economies (Romancov 2006).

All three Baltic States have been threatened by Russian companies with the interruption of energy supplies, ostensibly for nonpayment of past debts (INFO-TEK Agency 1994). The question arises whether the Russian firms that are cutting off the oil are acting independently or according to Russian state policy. The Russian government, in fact, has taken steps to control all strategic relationships, such as energy. Recent moves by Russian energy giants show that their intention is to increase the price of exports to market levels, even in the case of close allies, such as Belarus. This is a serious economic problem that all subsidized Russian gas importers will have to deal with eventually.

Gas giant Gazprom is increasingly a tool of the Russian government. Gazprom alone accounts for about 93 percent of Russian gas production (Romancov 2006). The Russian government owned 51 percent of Gazprom in 2005, and a former Russian prime minister sits on its board of directors. The president of another Russian oil company, Lukoil, indicated bluntly that by furthering his company’s interests, he was also furthering Russian state interests (Interfaks 1996). A firm such as Yukos, which resisted Moscow’s influence, recently came under intense Kremlin scrutiny when it was charged with tax evasion and its head, Mikhail Khodorkovsky, imprisoned, a move which the West sees as clearly politically motivated. Russia’s tying energy to foreign policy is further illustrated by a speech made by President Vladimir Putin shortly after he took office in 2000. At a gathering of Russia’s energy elite that year, he stated:

The state and also Russian embassies throughout the world must adopt an active lineage of defending the interests of Russian energy companies overseas, which must come from the principles of the geostrategic interests of the Russian federation. Similar goals are defined within the framework of the Russian energy strategy up to the year 2020, when it is explicitly stated that, with a new chapter in the development of Russia, the energy factor can and must strengthen the international influence of the country with a sizable political and economic effect and through harder, more operative, more considered politics and its respective mechanisms (Romancov 2006).

Such statements underscore Russia’s energy policy as an instrument of state power. This is also illustrated in the case of Mažeikių Nafta. Lithuania inherited from the Soviets the large Mažeikių Nafta oil refinery in northern Lithuania and decided to seek a Western company to operate it in order to provide a more secure oil refining capability, a move that Russia adamantly opposed. Negotiations began with the Williams Company in 1998, and during the 1998-1999 period, Russia had interrupted the supply to the refinery at least nine times, allegedly for technical reasons, but covertly to disrupt the negotiations with the American firm, so the Russian Lukoil Company could take full control of the country’s oil assets. In a similar move in 1999, Lukoil prevented a Kazakh oil firm from completing a contract to supply Mažeikių Nafta with oil, using the threat of having all the Kazakh shipments through a Russian pipeline halted if their deal with Lithuania moved forward (Smith 2005; Huang 2002).

Using moves neither overtly economic nor military, Moscow sent a former KGB officer to Lithuania as its ambassador during the height of the Lukoil-Williams negotiations to help prevent the deal from taking place and to support Lukoil’s takeover of the refinery. At the same time, rumors were leaked and spread by Lithuanian media of widespread corruption within Williams, thereby generating public opposition to the sale. Meanwhile, nationalist Lithuanian politicians began to openly criticize Lukoil and Moscow’s interference. Privately, Moscow indicated to the Lithuanian government that there would be serious damage to Russian-Lithuanian relations if the deal moved ahead. Moscow even sent a former energy minister to Latvia to convince that government to boycott oil shipments to Lithuania, in order to further pressure Vilnius to allow Lukoil to take over the refinery (Smith 2005; Huang 2002).

Russia has been successful in buying political influence. Parliamentary elections were held in Lithuania in 2000. Lukoil’s Baltic operating body, Lukoil Baltija, formed a company called “Vaizga” to funnel funds to political groups in Latvia and Lithuania. At least two members of the Lithuanian parliament have admitted to Western embassies that they had accepted these funds. Another example of Russian influence can be found in former President Rolandas Paksas. While Prime Minister, Paksas resigned over the Williams-Lukoil deal, alleging poor terms for Lithuania. When later elected president, he was impeached after less than a year in office, partly due to his ties to a Russian citizen, Yuri Borisov, whom the Lithuanian constitutional court found had blackmailed the former president. Borisov was a large contributor to Paksas’s presidential campaign and threatened to make the president a “political corpse” if he did not heed his wishes (Girdzijauskas 2004).

Many of the most powerful economic figures in Lithuania and other former Soviet states made their fortunes in the energy sector during the Soviet period, and have close ties to individuals in Gazprom. Additionally, many of these individuals held high-ranking political positions during the Soviet era. For example, the ethnic Russian and former Economics Minister, Viktor Uspaskich, came to Lithuania in 1985 to work for Gazprom. He has since become one of the country’s richest individuals, forming the popular Labor party, which almost succeeded in garnering the majority of votes in the 2004 parliamentary elections. Lithuanian nationalist politicians were appalled at the prospect of an individual with Russian citizenship and close political and business ties to Russia becoming the Prime Minister.

Russian energy policy was exerted more recently when Russian President Putin threatened to disrupt oil supplies to Lithuania if President Adamkus declined Putin’s personal invitation to attend the sixtieth anniversary of the end of World 70 War II. In a controversial move, on March 7, 2005, Adamkus and Estonia’s president jointly declined, stating that the end of World War II marked the beginning of almost fifty years of Soviet tyranny. Latvia’s president agreed to attend, perhaps due to a much larger Russian population. Yukos, the rebellious Russian oil company, which at the time was resisting Kremlin influence, jointly owned the Mažeikių Nafta refinery with the Lithuanian government. On March 18, 2005, Russian authorities stated that they intended to prevent Yukos from shipping crude oil from Russia to Mažeikių Nafta through the Russian pipeline.

Although the EU is clearly aware of such attempts by Moscow to place countries such as Lithuania under their sphere of influence, there are several reasons why it may be reluctant to act. First, Russia is still a more reliable source of oil for Western Europe than potentially politically unstable fuel-rich countries such as Venezuela and Indonesia, and those in the Middle-East. Secondly, Russia controls much of the increasing export of oil from the Caspian Sea through its pipelines. This oil could be interrupted by Russia, as it had done with Lithuania, causing economic havoc throughout the EU. The corollary effect of this is that Russia is again, as in the Lithuanian case, able to exert pressure on such transit countries as Kazakhstan, Azerbaijan, and Turkmenistan to not develop their own independent energy relations with the West. Third, and foremost, geography plays a major role; because Russia is much closer to Lithuania than many other oil-rich countries, so transportation costs are much less because the infrastructure is already in place. Keith Smith, a policy analyst at the Center for Strategic and International Studies and former American ambassador to Lithuania succinctly summarizes the situation: “By threatening to cut off energy supplies, Russia [could use] the ‘energy weapon’ to influence government decisions in the Baltic countries” (2005).

Solutions to Lithuania’s Energy Dependency

One solution for Lithuania now is the conservation of existing energy sources (Žvingilaitė and Moller 2004). The heating of residential buildings takes up a large proportion of the country’s energy needs. Thus, these authors advocate improving the energy efficiency of dwellings. Soviet-era residential “monoliths,” built during the 1960s through the 1980s were often poorly constructed and even more poorly insulated. Žvingilaitė and Moller write, “Some countries are becoming dependent on others concerning security of energy supply (importing fuels). [The] Energy sector has become [a] big issue in [the] political arena and the reason for tension in international relations” (p. 3). Žvingilaitė and Moller point out that several major objectives would be accomplished by focusing on energy conservation:

1. A reduced cost of energy to consumers.

2. A decrease in energy dependency on Russia.

3. A reduction in greenhouse gas emissions.

Niblett and his coauthors (2005) offer two policy suggestions to countries, such as Lithuania, that are at the mercy of Russia’s energy supply. First, they suggest these countries begin to trim their fuel consumption through greater assistance (i.e., imports) from more reliable sources, like Norway and the United States. While far from making Lithuania energy independent, it would force Moscow to acknowledge that both the United States and the European Union proper are closely watching Russia’s aggressive “foreign energy policy.” At the same time, Lithuania’s dependency also benefits oil-producing countries of the EU and the United States, by forcing Lithuania to seek greater ties to those countries’ resources.

Secondly, Niblett et. al. (2005) suggest greater transparency in the role that different Russian-owned energy companies play in the domestic policies of Lithuania. As previously indicated, this has become a major problem in Lithuania. Russian companies fund the Siloviki (former members of the Soviet nomenklatura), who in return allow Russian energy companies very loose restrictions in their dealings in the energy sector. It is precisely this lack of clarity in the country’s energy economy that is preventing some Western firms from investing more in Lithuania.

The authors additionally argue for larger storage capacities for those countries dependent on Russian crude oil. Just as a large storage capacity of water is useful during a period drought, a country like Lithuania could more easily weather an interruption in oil supply if it had a large stockpile on which it could rely. Lithuania could follow the example of the United States and other countries and create vast underground strategic reserves of oil for use in times of heightened demand or reduced supply.

Perhaps most importantly, Nisbett et. al. argue for a diversification of sources. Echoing economic sociologists Boswell and Kentor (2003), it is better to be reliant on multiple sources of crude than mainly or exclusively on one. The more diversified the access to resources, the less dependent Lithuania is on any one resource. This is especially true in the case of Lithuania’s dependency on Russian oil. Lithuania has indeed experimented with other forms of energy, with unsuccessful results. For example, Lithuania has attempted to use the environmentally disastrous Orimulsion for its oil-powered electrical plants. The country has also imported heavy fuel oils, but these are prohibitively expensive (Huang 1999a).

As a member of the European Union, Lithuania now has the backing of a large political bloc to achieve energy independence. Nesbitt et. al. (2005) indicate that the EU could put political pressure on Russia, to make its membership in the World Trade Organization, for example, contingent upon “playing fair” with the Baltic States, and more broadly, Central and Eastern Europe. An energy charter that assures the Baltic nations of uninterrupted crude oil from Russia, signed by all parties, would be a positive development for the region. However, at an informal EU-Russia energy summit in October 2006, President Putin made it clear that he would not sign such a charter in any case.

Nesbitt et. al. also indicate that some European Union countries, such as France, Italy, or Germany weaken the common EU front by negotiating their own bilateral trade agreements with Russia. A recent example of energy bilateralism 73 is the so-called “Putin-Schroeder Pact,” of 2005 that will link Russia with Germany via an oil pipeline under the Baltic Sea. The deal was finalized privately, without consultation with the countries bypassed, causing anger and frustration among the Baltic nations (Pavlovskis 2005). It reminded them that they, like in the Molotov-Ribbentrop pact of 1939, are once again being partitioned between the more powerful Eastern and Western powers. The secret Molotov-Ribbentrop meeting occurred between diplomats of Russia and Germany prior to World War II, when they agreed to divide the Baltic States between German and Soviet spheres of influence. Being a part of the EU and NATO changes dependency relations by reorienting military and political alliances to the West, but it has yet to reduce Lithuania’s energy dependence on other countries.

Conclusion

This essay on economic policy in Lithuania shows the relationship between energy, the economy, and geopolitical factors facing the country today. Although I suggest that Lithuania is extraordinarily dependent on Russian oil, I also point out the country’s move to try to reorient this dependency from East to West, thereby reducing dependency on Russia. Though all the Baltic countries have some degree of electrical generating capability, each has its weaknesses. For example, Latvia’s reliance on the Dauguva River’s hydroelectric power is reliant upon seasonal weather patterns. With the imminent closure of Ignalina in Lithuania, the country will be forced to rely on its other much smaller electrical generating plants. Unless Lithuania builds another Western-style reactor, it will certainly not be the Western analog to the regional power hub envisioned in the Soviet era.

This paper further illustrates the subtle means by which Moscow is extending its sphere of influence over the Baltic States. In what could be described as a new form of imperialism, Russian gas companies, such as Gazprom and Lukoil, have close ties to the Moscow political establishment. Russian oil companies that do not yield to Moscow’s wishes and pursue a more liberal, anti-Putin agenda, such as Yukos, are punished and their leaders (such as jailed Yukos head Mikhail Khodorkovsky) muzzled. Some Lithuanian politicians have continued to maintain close ties with Moscow, as illustrated by the dubious energy policies of Paksas, with his resistance to selling the Mažeikių refinery to a Western company, rather than a Russian one, and his later alleged ties to Russian organized crime.

Energy dependence is only one of several forms of dependency that Lithuania must navigate. Other areas of dependency Lithuania is involved in include economic and military dependence. It appears that history will again repeat itself, with the immediate fate of Lithuania in the hands of its more powerful neighbors.

WORKS CITED

Balčiūnas, P. 1999. “The Method of Analysis of Solar Energy Resources in Lithuania and Systems of Monitoring,” Solar and other Renewable Energy Sources for Agriculture. Raudondvaris: Lithuanian Institute of Agricultural Engineering. 12.

Boswell, T. and Kentor, J. 2003. “Foreign Capital Dependence and Development: A New Direction.” American Sociological Review. 68: 301-313.

Bradley, B. 2002. “Lithuania says EU Must Fund Nuclear Plant Closure.” Reuters, 16 May. Central Europe Review, 3 July 2000; 10 July.

Frierson, B. 2002. “Lithuania’s nuclear workers fear the future.” Reuters, 14 May.

Girzdijauskas, S. 2004. “The Impeachment of Lithuanian President Rolandas Paksas,” Joint Baltic American National Committee. 5: April 7.

Hagland, J. 2000. “The Norwegian Oil and Gas Adventure.” Ministry of Foreign Affairs, Norway.

Huang, Mel. 1999a “The Amber Coast: Lithuania’s Nuclear Dilemma.” Central European Review. Vol. 0, No. 23.

______. 1999b. “Waiting for the Ring.” Financial Times - Power in Eastern Europe. 27 May 1999, p. 17.

______. 2002. “Electricity in the Air: The Real Power Politics in the Baltics.” Conflict Studies Research Center. Defense Academy of the United Kingdom (Conflict Studies Research Center). Surrey, England.

INFO-TEK Agency. 1994. “Brief Summary of Results of Operations of Russian Fuel-Energy Complex in January-April 1994.” No. 10, October 1994, pp. 27-29.

Interfaks-aif. 1996. Interview with Vagit Alekperov, President of LUKOIL. May No. 20, p. 5.

Izvestia. 1993. June 30. p. 1. “Russian gas deliveries to Baltic Regions Halted.” (CDPSP, Vol. XLV, No. 26).

Kirby, D. 1995. The Baltic World 1722-1993. London: Longman.

Lithuanian National Radio. 1992a. February 28. (SWB SU/1318, 2 March 1992, p. A2/3).

Lithuanian National Radio. 1992b. August 1992. (SWB SU/1473, 31 August 1992, p. A2/A3).

Misiūnas, R. and Taagepera, R. 1993. The Baltic States: Years of Dependence, 1940 - 1990. University of California Press, Berkley, 1993.

Niblett, R., Nurick, R., Smith, K. 2005. Russian Energy and Politics in the Baltics, Poland and Ukraine. Center for Strategic and International Studies: The Europe Program. Congressional Staff Forum.

Pavlovskis, V. 2005. Baltic Caucus Update. November.

Romancov, M. 2006. “A Different Cold War.” New Presence: The Prague Journal of Central European Affairs. Vol 8, Issue 4.

Smith, K. 2005. Russian Energy Politics in the Baltics, Poland, and Ukraine: A New Stealth Imperialism. Center for Strategic and International Studies: The Europe Program. Congressional Staff Forum.

United States Department of Energy’s Office of Fossil Energy. 2005. Website: http://www.fe.doe.gov/index.html

Žvingilaitė, E. and Moller, Bernd. 2004. “Improving the Energy Performance of Buildings: A Lithuanian Case.” Aalborn University (Unpublished manuscript).